In this article we investigate the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO): what it is, how it impacts the weather, and how we can use it in long-range weather forecasting.

North Atlantic Oscillation: Introduction

The North Atlantic Oscillation is the most influential atmospheric climate index (climate cycle or teleconnection) over the North Atlantic sector, and can be thought of as the Atlantic sector of the Arctic Oscillation. The state of the NAO influences weather conditions on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean with impacts mainly occurring in the Eastern US, as well as Western Europe.

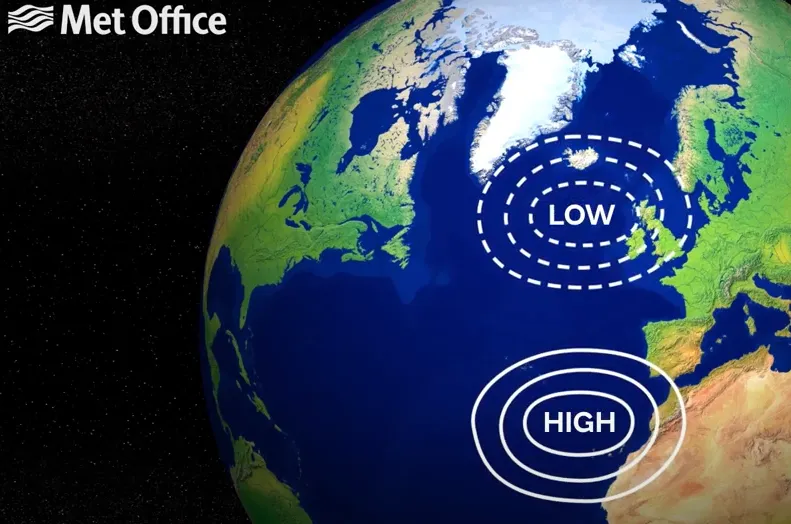

On average we find a surface pressure dipole over the North Atlantic Ocean. A low pressure is centred between Greenland and the United Kingdom (known as the Icelandic Low), and high pressure is centred to the southwest of Europe (known as the Azores High). The NAO index measures the departure from this normal pressure pattern between the two pressure centres.

The North Atlantic Oscillation is defined in various ways. One simple method is to consider the surface pressure at two reference points; typically Reykjavík, Iceland in the north, and Lisbon, Portugal in the south. NOAA relies on a statistical method, called empirical orthogonal functions (EOFs), which represents the broad pressure pattern over the North Atlantic at the 500mb level in the atmosphere (approximately half way up in the troposphere).

The average NAO condition results in prevailing westerly flow into Western Europe, which has a moderating effect on surface temperatures. The Atlantic Ocean is relatively cool compared to continental Europe in summer, and so a westerly wind has a cooling influence and prevents excessive heat events. In winter, the Atlantic Ocean is relatively warm compared to continental Europe, and so a westerly wind has a warming influence and keeps the colder weather at bay.

The strength of the westerly flow also determines the strength, frequency and penetration of extratropical storms that routinely track into Western Europe from the Atlantic.

North Atlantic Oscillation: Positive Phase

When the pressure difference between the Icelandic Low and the Azores high is greater than normal, the North Atlantic Oscillation is said to be positive. A positive NAO leads to a stronger westerly flow into Western Europe; the more positive, the more this is true.

The World Climate Service has developed a powerful data mining system that enables users to quickly explore the impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation, and many other indices, by phase for each month of the year, showing impacts on all the major weather variables all around the globe. The maps featured in this article can be produced in just a few clicks of the mouse.

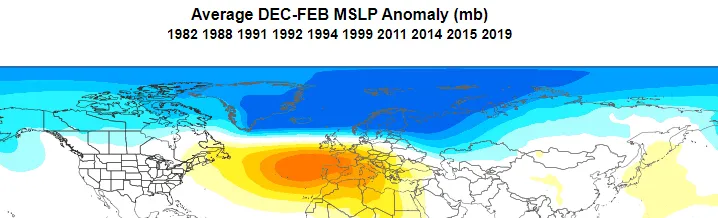

Fig. 2

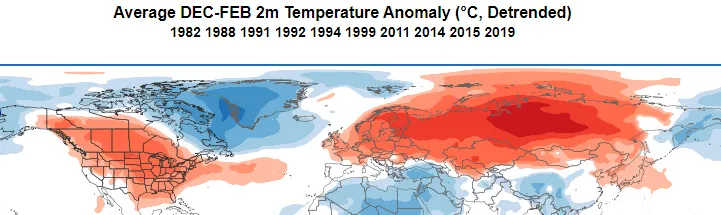

Fig. 3: World Climate Service average surface pressure anomaly (Figure 2) and the corresponding average temperature anomaly (Figure 3) during a strongly positive North Atlantic Oscillation in winter

The strong flow around the Atlantic pressure anomaly drives mild oceanic airmasses into North America, Europe, and much of Russia.

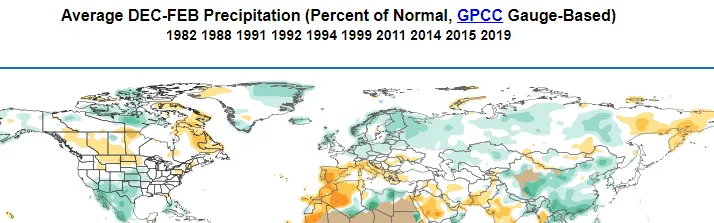

Fig. 4: World Climate Service rainfall average anomalies during a strongly positive North Atlantic Oscillation in winter

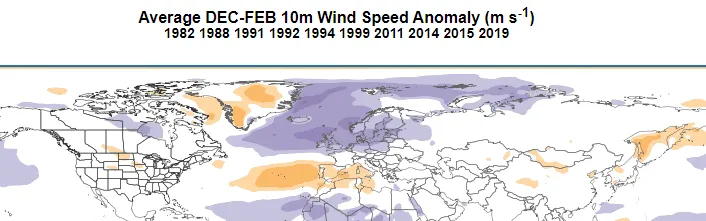

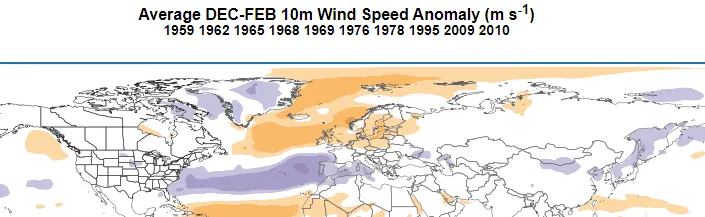

Fig. 5: World Climate Service wind speed average anomalies during a strongly positive North Atlantic Oscillation in winter

Northern Europe is typically wet and windy, while Southern Europe is typically dry and calm. There is also a dipole evident of the Central US, with the North dry and the South wet.

North Atlantic Oscillation: Negative Phase

Conversely, when the pressure difference between the Icelandic Low and the Azores high is smaller than normal, the North Atlantic Oscillation is said to be negative. A negative NAO leads to a weaker westerly flow into Western Europe; the more negative, the more this is true.

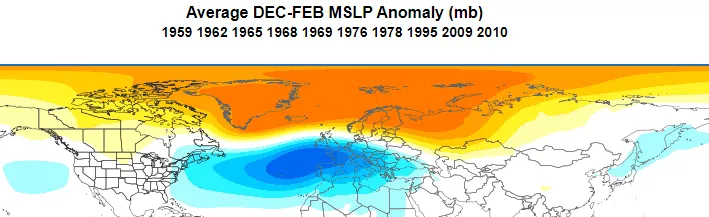

Fig. 6

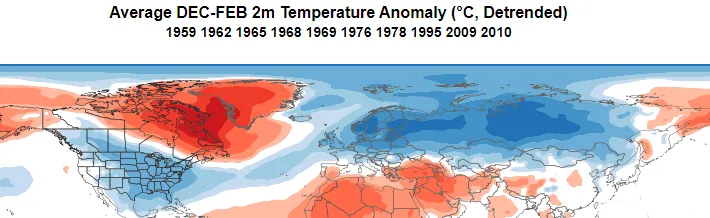

Fig. 7: World Climate Service average surface pressure anomaly (Figure 6) and the corresponding average temperature anomaly (Figure 7) during a strongly negative North Atlantic Oscillation in winter

The weak westerly flow over the Atlantic sector prevents mild oceanic airmasses being driven into North America, Europe, and much of Russia, and thus these areas are, on average, colder than normal.

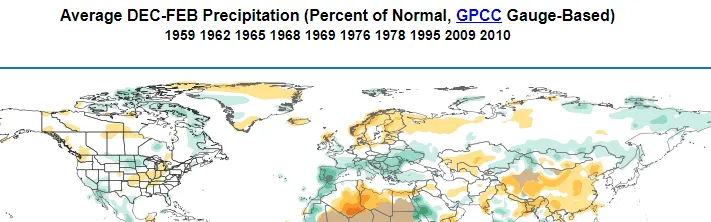

Fig. 8: World Climate Service rainfall average anomalies during a strongly negative North Atlantic Oscillation in winter

Fig. 9: World Climate Service wind speed average anomalies during a strongly negative North Atlantic Oscillation in winter

Northern Europe is typically dry and calm, while Southern Europe is typically wet and windy. There is also a dipole over the Midwestern US where the North is wet and the South is dry.

North Atlantic Oscillation: Importance to Long Range Forecasting

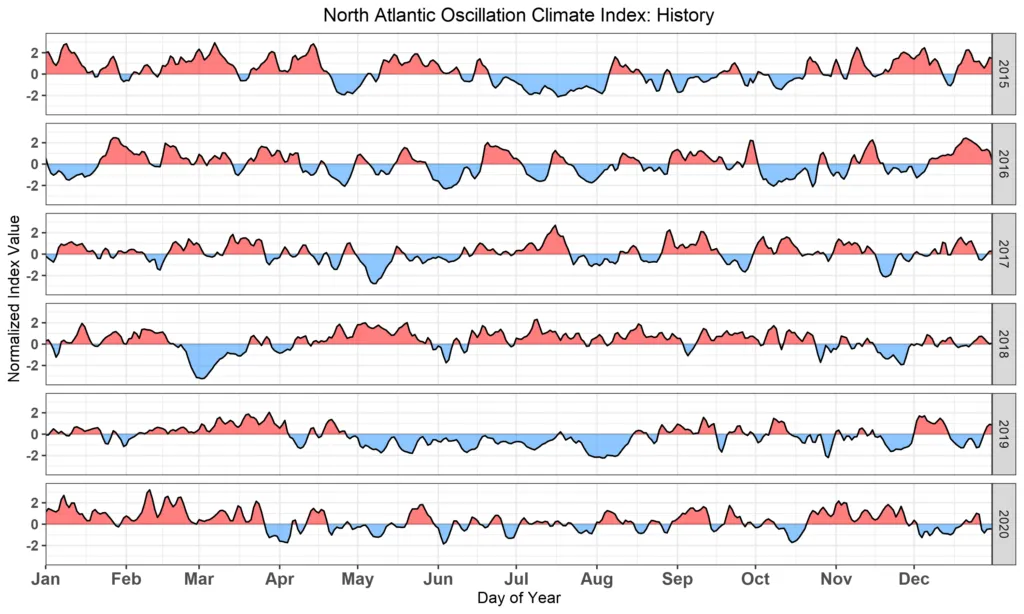

The North Atlantic Oscillation typically remains in a given phase anywhere from a few days, to a few months, as seen in the 5-year NAO history (Figure 10). In winter a strong NAO phase in either direction tends to persist for many weeks and can often be forecasted confidently with lead times of 2 to 3 weeks.

The NAO is a key indicator in long range forecasting because both phases of the NAO show a high correlation to temperature and rainfall patterns in the mid-latitudes in winter.

The World Climate Service includes information regarding the recent variations in the NAO.

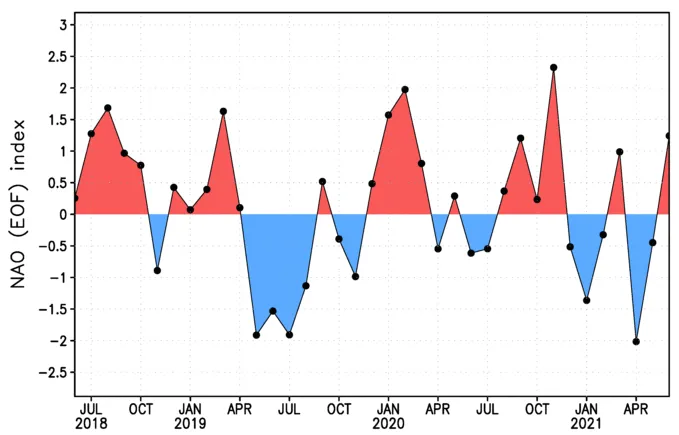

Fig. 11: World Climate Service chart showing the variation of the North Atlantic Oscillation since summer 2018

North Atlantic Oscillation and the Stratospheric Polar Vortex

High above the tropospheric polar vortex, a vortex also forms in the thin stratospheric air each winter. The Stratospheric Polar Vortex (SPV) develops in the fall and dissipates in the spring, but otherwise behaves much like the tropospheric vortex in the sense that spins from west to east (i.e., counter-clockwise) when looking down on the North Pole. The SPV is important because it can influence the North Atlantic Oscillation below.

When the SPV is stronger than normal it tends to support a positive North Atlantic Oscillation. The reverse is also true; a weaker than normal SPV is more likely to coincide with a negative North Atlantic Oscillation. Around every two years, the SPV temporarily collapses in a process known as sudden stratospheric warming. When this happens, the North Atlantic Oscillation often shifts more negative for anywhere between a few weeks and a few months.

North Atlantic Oscillation: Conclusion

The North Atlantic Oscillation is a variation of the relative strength between the Icelandic Low and the Azores high. The NAO is very important as it determines the strength of the westerly flow across the North Atlantic, which in turn influences the weather across much of the mid-latitudes.

The North Atlantic Oscillation can persist in a given phase for weeks or even months during winter, and can also be modified by the Stratospheric Polar Vortex – making it a key factor in long range weather forecasting.